As we have talked about the General Theory of Relativity, the significance of the solar eclipse has come up since it gave accuracy to Einstein's theory. Professor Wheeler spoke about witnessing the total solar eclipse a couple of years ago the strange behavior of animals that occurred at the point of totality. I had previously heard of some of the weird things animals do during these types of episodes, but my interest was renewed recently so I decided to look into it more

Different animals have different reactions to the eclipse. As mentioned in class, crickets will come out and start chirping as if it is nighttime once the moon blocks the sun. Also, bees stop their buzzing, cows stop their grazing, and all return to their respective dwellings en masse. Other creatures, such as spiders, will take down their webs as they would normally do at night, only to come to the sad realization that they must reconstruct them again without a night's rest minutes later. And while more intelligent animals are aware that this occurrence is a fluke, other animals genuinely perceive it is as being night and change their behavior accordingly. In the back of my mind I know animals' sense of time is very different from humans', but it is particularly intriguing how in-tune animals necessarily are with the natural universe and how much we have removed ourselves thanks to our brains and inventions.

One article I read indicated how hard it is to empirically gather data on animal behavior during eclipses. Most evidence comes from anecdotal evidence, perhaps because people are too busy looking at the sky to do research.. (a joke). However, science, in staying true to inductive reasoning, hopes to gather more accurate data through the power of collaboration. Scientists have developed an app which allows users to document their observations of animals during eclipses in order to identify clear patterns of animal behavior. As of today, it is hard to obtain concrete, scientific evidence for these phenomena. More research into this study is one aspect of technology that would be interesting to follow going into the future.

Foundations of Mathematical Thought - Brian Weir

Thursday, January 30, 2020

Tuesday, January 28, 2020

Should We Care About Extinction/The AI Hilbert Problems

A lot of blogs and class discussion have been about AI. It is always stimulating to me to discuss what the future might look like given our current trajectory as a species. Sometimes though, things take a darker direction and I wonder: what if the ways we are threatening our existence aren't such a big deal? I mean, if destroying the planet or surrendering ourselves to the power of AI is where our evolution has taken us, how concerned should we be? Natural selection, right? Species go extinct every day. If we can't (or won't) fix our problems, then that settles it - we lose! Can self-inflicted annihilation be our natural course?

My retort would be that these issues do not only affect humans and that we maybe should not act like they do. I am not sure what moral responsibility we have for everything around us like plants, animals, and other natural features, but it seems like we should not be so selfish and it also seems like humans are capable of innovating safely.

I made a few Google searches on this idea of humans absolving ourselves from various threats to our species. While I did not find anything directly related to this concept, there are clearly prominent public figures who vouch for lengthening our existence. For instance, TIME's most recent Person of the Year is an environmental activist concerned for our future and presidential candidates are emphasizing the importance of environmental sustainability.

Also, a few years ago, popular thinkers Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking supported a Hilbert-esque list (it contains exactly 23 items, just like Hilbert's) laying out guidelines for how to approach the development of AI in the future. The guidelines are broken up into three parts: Research issues, ethics and values, and longer-term issues. In each category, there is a motif of responsibility. Humans on the aggregate are responsible for how we develop AI and, it seems, cooperation will need to extend beyond countries' borders in order to safely develop AI. While there may seem to be pessimism regarding AI, it could be something that unifies people instead. Of the items on the list, I like number 19 which states that we should not make assumptions about AI since we cannot know its full capabilities. While the list is helpful, I think it will be hard to follow every principle because new issues will arise that we have not yet considered; the list may need to expand.

My retort would be that these issues do not only affect humans and that we maybe should not act like they do. I am not sure what moral responsibility we have for everything around us like plants, animals, and other natural features, but it seems like we should not be so selfish and it also seems like humans are capable of innovating safely.

I made a few Google searches on this idea of humans absolving ourselves from various threats to our species. While I did not find anything directly related to this concept, there are clearly prominent public figures who vouch for lengthening our existence. For instance, TIME's most recent Person of the Year is an environmental activist concerned for our future and presidential candidates are emphasizing the importance of environmental sustainability.

Also, a few years ago, popular thinkers Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking supported a Hilbert-esque list (it contains exactly 23 items, just like Hilbert's) laying out guidelines for how to approach the development of AI in the future. The guidelines are broken up into three parts: Research issues, ethics and values, and longer-term issues. In each category, there is a motif of responsibility. Humans on the aggregate are responsible for how we develop AI and, it seems, cooperation will need to extend beyond countries' borders in order to safely develop AI. While there may seem to be pessimism regarding AI, it could be something that unifies people instead. Of the items on the list, I like number 19 which states that we should not make assumptions about AI since we cannot know its full capabilities. While the list is helpful, I think it will be hard to follow every principle because new issues will arise that we have not yet considered; the list may need to expand.

Thursday, January 23, 2020

Planck Lengths and the Scale of the Universe

In class and on a homework assignment, we discussed the Planck length and Planck time. After looking up what these things are, I was dumbfounded since there is clearly a lot I do not understand about physics. Specifically, since a Planck length cannot be halved, how can it actually be considered a length and not something else entirely? It's clearly hard to imagine and of course impossible to observe with our own eyes. The best we can do is compare it to things we know of that are also small, whether it be a mouse, or an ant, or a cell, or a particle, or an atom. But for any of these, do we really have a good sense of their relative size? The website scaleofuniverse.com does the imagining for us, and will make you rethink what is small and what is large. It is pretty remarkable to scroll through the different items and get a better sense of what is out there in the universe and how we (and many other things) stack up against it. After viewing this, I understand better why Pluto was demoted to a dwarf planet. Here is another part of the model I enjoyed:

I think this site is worth checking out, especially if you enjoy thinking about your (in)significance in the universe. I'm kidding, but the first time I saw this I was pretty blown away. I could go on about some of the most interesting comparisons, but I'd hate to take away all the fun.

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

Matryoshka Dolls in Math, Art, and Computer Science

Yesterday in class I enjoyed learning about outlining using a top-down approach. I also consider this approach to be useful in essay writing and Google Drive organizing, but after the wedding analogy, I see other ways the strategy can be applied in other areas and another concept that it reminds of, namely Russian nesting dolls.

It seems to me that the top down approach makes each subsequent step easier to manage since, if done right, one cannot get ahead of their self; the previous step is necessary to get to the next step and the step after that. This process, as well as the idea that there are several small subsets underneath an umbrella term (e.g., the ceremony, reception, and honeymoon are all parts under the "wedding" umbrella), remind me of these dolls.

Each hollow doll contains another doll within it, which also contains many dolls within itself as well. To me, these dolls seem somewhat Euclidean. The first doll could represent postulate 1 since it is necessary to interact with it to continue with a process. That is just my opinion because, from what I found in my research, these dolls did not originate in order to teach mathematical concepts. They are, however, referenced in order to teach about recursion and fractals in mathematics, both things we have learned about in class. More research on recursion led me to this interesting image below which shows a picture within a picture within a picture... do you see it?

Each hollow doll contains another doll within it, which also contains many dolls within itself as well. To me, these dolls seem somewhat Euclidean. The first doll could represent postulate 1 since it is necessary to interact with it to continue with a process. That is just my opinion because, from what I found in my research, these dolls did not originate in order to teach mathematical concepts. They are, however, referenced in order to teach about recursion and fractals in mathematics, both things we have learned about in class. More research on recursion led me to this interesting image below which shows a picture within a picture within a picture... do you see it?

|

| These can also be known as "Russian (tea) dolls, nesting dolls, and more. |

Each hollow doll contains another doll within it, which also contains many dolls within itself as well. To me, these dolls seem somewhat Euclidean. The first doll could represent postulate 1 since it is necessary to interact with it to continue with a process. That is just my opinion because, from what I found in my research, these dolls did not originate in order to teach mathematical concepts. They are, however, referenced in order to teach about recursion and fractals in mathematics, both things we have learned about in class. More research on recursion led me to this interesting image below which shows a picture within a picture within a picture... do you see it?

Each hollow doll contains another doll within it, which also contains many dolls within itself as well. To me, these dolls seem somewhat Euclidean. The first doll could represent postulate 1 since it is necessary to interact with it to continue with a process. That is just my opinion because, from what I found in my research, these dolls did not originate in order to teach mathematical concepts. They are, however, referenced in order to teach about recursion and fractals in mathematics, both things we have learned about in class. More research on recursion led me to this interesting image below which shows a picture within a picture within a picture... do you see it?

The final connection between these Russian dolls and this class has to do with computer science. Last year when taking Principles of Computer Science, I got the sense there was something representing a Russian doll when I would (attempt to) construct things like classes or functions. From what I understand, these organizational tools of computer science are groups that hold smaller things inside of them and are themselves a necessary part of a larger program. I had not heard of a comparison between computer science and Russian dolls until I looked it up this morning and found a few websites that do indeed recommend using Russian dolls as an analogy for recursive functions.

Monday, January 20, 2020

Certainty in Economics

In our pursuit of finding out what truth means in this course, we have touched on the concepts of certainty and uncertainty. A couple times, our professor has remarked that if we cannot even be certain about things in math, it would likely be much harder to identify truth in fields like political science, sociology, or economics.

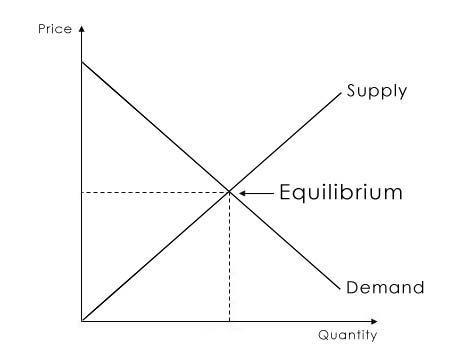

I am intrigued by this question because, having taken several economics courses, I have wondered about its certainty, too. In economics, graphical models representing the behavior of firms and individuals are staples that can represent a lot of things, but most notably the laws of supply and demand. This model indicates that as the price for an item decreases, the buyers will want to buy more. The inverse relation is true for suppliers of the item in that they will produce more of something if they can get more money for doing so. Here is a graphical representation that you will remember if you took economics in high school:

What does this have to do with certainty? I used to struggle in economics because I felt like we cannot be certain about human behavior enough to call this model a "law". A real-world counter example to the law would be in the case of art collectors who often prefer to buy the most expensive art to flaunt their wealth.

Evidently, this law is not certain since the model only exists in an imaginary world. In economics models, economists can create their own worlds and set their own rules for them, almost like what Euclid did. Within these worlds, they make assumptions that people making transactions are rational, make decisions based on their own self-interest, that buyers are rational, and that sellers are transparent. It reminded me that we can imagine anything even if does not exist in reality, such as infinite numbers, infinite planes, or lines that do not take up space. In the case of economics, models sometimes merely serve as helpful guides and not 100% accurate representations of reality 100% of the time. Despite their made-up rules, these models work well enough to rely on to make predictions about people's behavior. Less is at stake by an inconsistent economics graph than a mathematical proof; the entire framework of economics could still be salvaged if people and markets significantly change. For math, one wrong proof can take down every invention of math that came after it.

Friday, January 17, 2020

Proposition 8

I have found the propositions to be mostly straightforward especially when constructing along with the instructions. It is satisfying when I am able to finish and understand them. In proposition 8, however, the proof section starting with "Suppose, for contradiction, that the vertex C does not coincide with F." was actually difficult for me to understand at first and required more time to understand. After talking the proposition over with classmates, watching a video, and thinking about it myself for a while, I think I internalized the basic meaning of proof by contradiction.

While I knew it was a proof by contradiction, it was not making sense as to why we should assume something wrong (the contradiction). I thought it was obvious that C and F lined up when I moved the triangles - they were supposed to. I think my presumption stemmed from my drawing in which the triangles looked very similar to each other. As a result of their appearance, it was hard to imagine the points not coinciding. Once it clicked that the goal is to prove the opposite of the contradiction, the rest of the proof made sense. While it took me more time than it probably should have, I feel satisfied having worked through it and having a better understanding as a result.

While I knew it was a proof by contradiction, it was not making sense as to why we should assume something wrong (the contradiction). I thought it was obvious that C and F lined up when I moved the triangles - they were supposed to. I think my presumption stemmed from my drawing in which the triangles looked very similar to each other. As a result of their appearance, it was hard to imagine the points not coinciding. Once it clicked that the goal is to prove the opposite of the contradiction, the rest of the proof made sense. While it took me more time than it probably should have, I feel satisfied having worked through it and having a better understanding as a result.

Thursday, January 16, 2020

Future Postcards from the Past

In Wednesday's class we discussed predictions for the future, namely the sorts of things we do today that we may frown upon in future iterations of society. In the homework due for that day, we researched the 14th Amendment and the newly-defined citizenship rights. While reading, I had wondered about who we are excluding today. My immediate thought was the homeless or those in poverty, but I also recalled hearing about how our current treatment of animals is likely to be viewed with scorn in the future. Sure enough, the latter thought was echoed again during class.

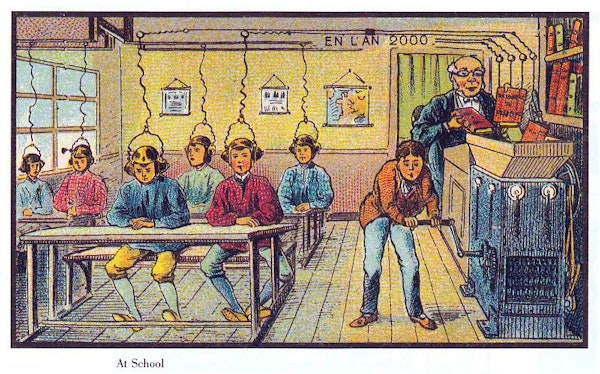

While thinking about our discussion later in the day, I recalled back to the class I took last year during J-Term, Explorations in Political Economy for the 21st Century *inhales deeply*. This class was essentially about looking at the past and present in order to think about the future more clearly. On the first day of class, the professor used an interesting device to think about future political economy: century-old postcards. In 1900, a popular postcard theme was futurist art. These postcards depicted images of what life in the year 2000 may look like. It was interesting to see how accurate the predictions were conceptually, but how they missed the mark in terms of how they were manifested. I've included some examples below. I find it to be a lot of fun breaking down what they got right and wrong and in what ways and why they might have made such predictions in the first place. It seems to me that we can predict concepts pretty well, but things will look a lot different than how we imagine they will (see helicopter image). Looking back at them I'm reminded again of a recurring idea in this class: humans move forward in knowledge step-by-step. In 1900, there was a lot that either had not been invented or was otherwise impossible to predict without other innovations to build upon.

While thinking about our discussion later in the day, I recalled back to the class I took last year during J-Term, Explorations in Political Economy for the 21st Century *inhales deeply*. This class was essentially about looking at the past and present in order to think about the future more clearly. On the first day of class, the professor used an interesting device to think about future political economy: century-old postcards. In 1900, a popular postcard theme was futurist art. These postcards depicted images of what life in the year 2000 may look like. It was interesting to see how accurate the predictions were conceptually, but how they missed the mark in terms of how they were manifested. I've included some examples below. I find it to be a lot of fun breaking down what they got right and wrong and in what ways and why they might have made such predictions in the first place. It seems to me that we can predict concepts pretty well, but things will look a lot different than how we imagine they will (see helicopter image). Looking back at them I'm reminded again of a recurring idea in this class: humans move forward in knowledge step-by-step. In 1900, there was a lot that either had not been invented or was otherwise impossible to predict without other innovations to build upon.Something I thought of that we might look back at curiously is the way we educate. I obviously cannot be sure, but I think it might have something to do how we organize students into grade levels by age and not by skill. It's not something I have thought hard about but it came to mind. To the left is a postcard about education in which information appears to be downloaded into children's brains. Is it really too far off?

There are more postcards like these online that I would recommend checking out if interested. Below are some more to ruminate on and/or spark discussion .

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Animals During Eclipses

As we have talked about the General Theory of Relativity, the significance of the solar eclipse has come up since it gave accuracy to Einste...

-

On the second day of class we were discussing the Fibonacci sequence and the rabbit problem. I think that gaining a full understanding of...