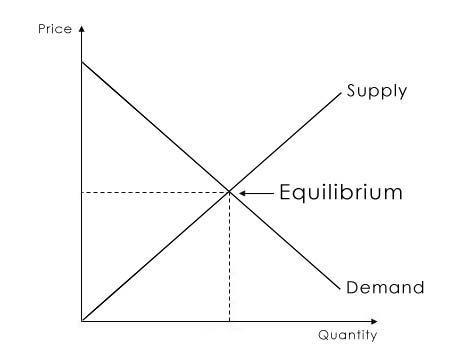

I am intrigued by this question because, having taken several economics courses, I have wondered about its certainty, too. In economics, graphical models representing the behavior of firms and individuals are staples that can represent a lot of things, but most notably the laws of supply and demand. This model indicates that as the price for an item decreases, the buyers will want to buy more. The inverse relation is true for suppliers of the item in that they will produce more of something if they can get more money for doing so. Here is a graphical representation that you will remember if you took economics in high school:

What does this have to do with certainty? I used to struggle in economics because I felt like we cannot be certain about human behavior enough to call this model a "law". A real-world counter example to the law would be in the case of art collectors who often prefer to buy the most expensive art to flaunt their wealth.

Evidently, this law is not certain since the model only exists in an imaginary world. In economics models, economists can create their own worlds and set their own rules for them, almost like what Euclid did. Within these worlds, they make assumptions that people making transactions are rational, make decisions based on their own self-interest, that buyers are rational, and that sellers are transparent. It reminded me that we can imagine anything even if does not exist in reality, such as infinite numbers, infinite planes, or lines that do not take up space. In the case of economics, models sometimes merely serve as helpful guides and not 100% accurate representations of reality 100% of the time. Despite their made-up rules, these models work well enough to rely on to make predictions about people's behavior. Less is at stake by an inconsistent economics graph than a mathematical proof; the entire framework of economics could still be salvaged if people and markets significantly change. For math, one wrong proof can take down every invention of math that came after it.

You've definitely hit on the weakness of classical models in economics. The assumption is that people are rational and take behaviors that are in their best interest, but in fact, people in general don't do this; that is, people do self-destructive stuff all the time and don't even realize it.

ReplyDeleteBut could there be a model that makes the assumption that people are going to behave irrationally? I think so, as long as we are predictable in our irrationality. There is hope for a science of economics.

I have already been interested in rational choice theory. It seems to me after studying Political Science for four years is that if you can be certain about one thing, it's the people are unpredictable and no model can ever hope to quantify them correctly. Some leaders have better instincts, but it's still a roll of the historical dice.

ReplyDelete